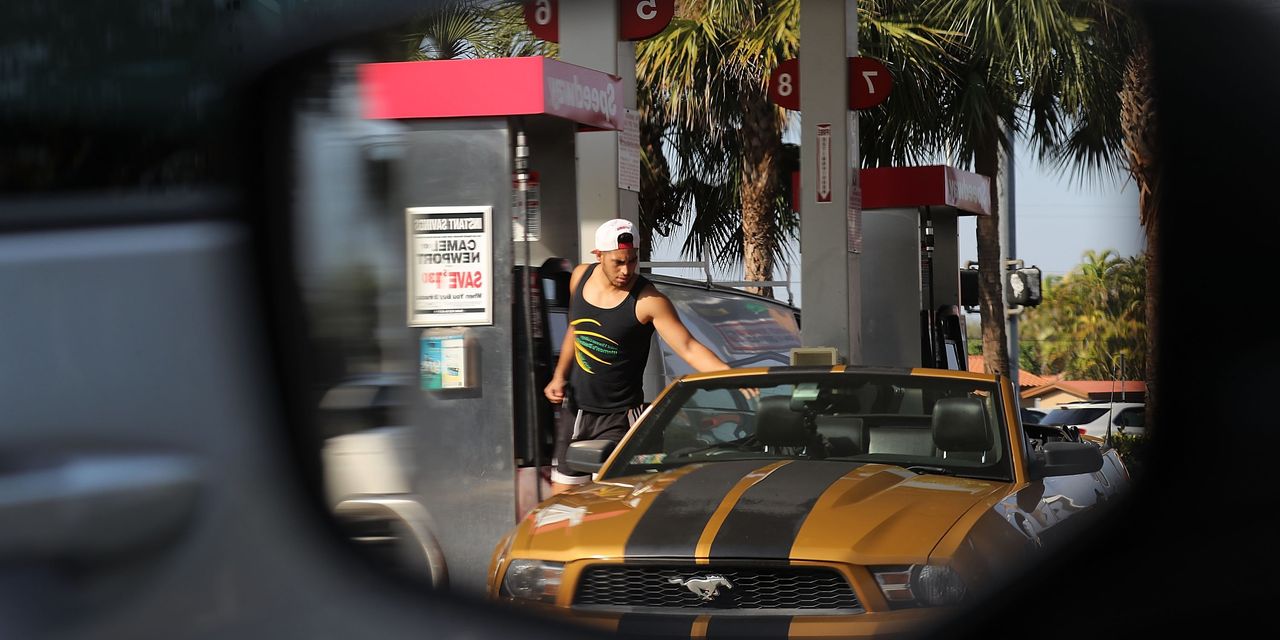

Retail gasoline prices may have already seen their peak for the year, but the potential for a “higher high” at the pump remains as drivers head into the U.S. summer driving season.

U.S. gasoline prices hit a peak of $3.6855 a gallon on April 20, and that looks to be the top of the market for the first half of the year, said Tom Kloza, global head of energy analysis at the Oil Price Information Service (OPIS), a Dow Jones company. “Prices have come down at a glacial pace since that date, but there is a strong history of peak prices arriving well before many Americans take to the road.”

The Memorial Day holiday on May 29 traditionally marks the start of the summer driving season, though the U.S. Energy Information Administration defines the driving season as April 1 through the end of September.

This year presents plenty of upside price risk during the peak driving weeks, which encompass the period when schools close and extends into early August when school tends to resume for southern and Midwestern regions, said Kloza. Risks of higher gasoline prices are “quite considerable for the remainder of August and September thanks primarily to the risks commensurate with peak [Atlantic] hurricane season.”

On Tuesday, the national average for regular unleaded gasoline prices stood at $3.531 a gallon, according to AAA. That’s down from $3.669 a month ago and $4.483 a year ago. Those prices are a far cry from last year’s record high of $5.016 on June 14.

Read: Gasoline prices may have already reached a summer-season peak

Kloza said that the base case for OPIS points to the April 20 gasoline price as the most likely high for 2023, but he offered several reasons why the potential for higher prices “shouldn’t be ignored.”

Among those factors, hurricane impacts are “by far the most serious threat,” he said.

In the last five years, some refineries have closed in California, New Mexico, Pennsylvania and other locations, said Kloza. Additions to U.S. refining, meanwhile, have been seen almost exclusively on the “Texas and Louisiana coastal real estate,” with those two states seeing a refining capacity increase of more than 400,000 barrels a day so far this year.

That’s “good news — unless it gets threatened or knocked out by hurricane probability cones,” he said. In 2023, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas account for about 9.7 million barrels a day of U.S. refining capacity. That’s up from 8.1 million barrels of refining capacity from those four states in 2005, the year of Hurricane Katrina.

Appreciation in the price of crude oil would be another risk factor for higher fuel prices.

Prices for U.S. benchmark West Texas Intermediate

CL.1,

CLM23,

and global benchmark Brent

BRN00,

BRNN23,

crude have been “sheared lower thanks to tectonic shifts of macroeconomic plates,” said Kloza.

The Chinese economic recovery after lifting COVID-19 restrictions has been slow, he said. Still, even some of the most bearish crude-oil analysts believe that the third quarter of 2023 presents the most “hospitable environment for crude-oil price appreciation.”

An $11 a barrel increase in Brent prices from its current level would lift the cost of making gasoline by about 26 cents a gallon, said Kloza.

The stability of the U.S. electricity grid is another key concern for the gasoline market. Many Gulf Coast and California refineries have cogeneration equipment that would allow them to generate power during brown-outs, or when the local grid is compromised, but most refineries don’t have this capability, said Kloza. “Power outages can disable large refineries over a period of days or weeks” and when a refinery suddenly loses power, procedures dictate several days of start-up activities.”

Exports of gasoline are also a big concern. The market may be “looking at the most robust foreign demand for gasoline in our lifetime and this could be an ongoing feature,” Kloza said.

Much of the gasoline produced in Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi moves to Latin America, as refining capacity in South America has dropped, he said, thanks to troubles in Venezuela including poor maintenance.

Meanwhile, motor gasoline inventories are “quite low,” and that could also send prices for the fuel higher, he said.

The U.S. currently has just under 220 million barrels of gasoline in storage, said Kloza, citing data from the Energy Information Administration. That compares to 225 million barrels one year ago, and 236 million barrels in 2021. High interest rates tend to dissuade companies from carrying additional inventory, said Kloza.

He also warned about what he referred to as the “Easter Church Syndrome.”

“ “Very high domestic [gasoline] demand, combined with brisk exports, and a threat to U.S. refining production could, unfortunately, live up to the characterization of a ‘perfect storm’” for higher prices. ”

He explained that the U.S. isn’t built with any safeguards for supply cushions during the “heyday of summer,” and that’s similar to the way churches aren’t built to deal with Easter Sunday crowds.

“Very high domestic [gasoline] demand, combined with brisk exports, and a threat to U.S. refining production could, unfortunately, live up to the characterization of a ‘perfect storm’” for higher prices, he said.

Read the full article here